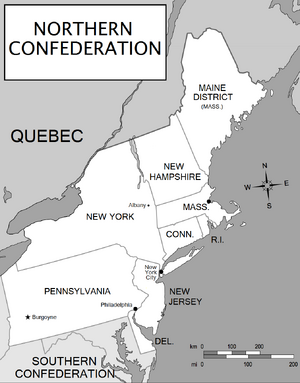

The Northern Confederation was one of the five original confederations that made up the Confederation of North America under the Britannic Design. Its capital and largest city is New York City, New York. The chief executive of the N.C. is the Governor of the Northern Confederation, and the legislature is the Northern Confederation Council.

As originally drafted, the Britannic Design would have had three confederations, with the New England provinces of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut originally called the Northern Confederation and the middle provinces of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware forming the Central Confederation. However, when the Design was being debated in the House of Lords, some of the members feared that the New England provinces would be prone to renewed rebellions, so it was decided to combine the proposed Northern and Central Confederations under the former's name.

Dickinson and Clinton[]

John Dickinson.

The first Governor-General of the N.C., John Dickinson of Delaware, was sworn in on 2 July 1782, the day the Design went into effect. Dickinson remained in office for less than a year and a half before being appointed to replace General John Burgoyne as Viceroy after the latter's death in September 1783. As Governor General, Dickinson oversaw the transition from martial law under Generals Burgoyne and William Howe to civilian rule. His most pressing problem was an ongoing insurrection in the Green Mountain area of New Hampshire led by several members of the local Allen family. General Howe had been unable to put down the Green Mountain insurrection, in spite of repeated military expeditions to the area.

Dickinson was succeeded as head of the N.C. by George Clinton, who like Dickinson had taken part in the North American Rebellion. Under Clinton, the N.C. experienced steady economic growth as immigration increased Pennsylvania's grain production, and British investment in Massachusetts textile mills brought prosperity there. New York City outgrew Boston as an export terminus for the confederation's products, as well as becoming the social and financial center of the N.C. Sobel quotes Clinton expressing relief over the failure of the Rebellion: "We may thank Providence the Rebellion did not succeed. Cast adrift on a sea of international intrigue, we would have foundered and been destroyed. Our present prosperity can be ascribed to our harmonious relations with other parts of the Empire, and the protection of the Royal Navy. Together we control a continent, perhaps the world. Singly, we would perish before those envious of our wealth."

George Clinton.

Clinton came into conflict with Theodorick Bland, the Governor of Virginia. Although Bland had also participated in the Rebellion, serving in the Continental Army under George Washington, he had come to reject its ideals by the 1780s. He spurned efforts by Dickinson and Clinton to promote inter-confederation cooperation, and instead blamed Northerners for the outbreak of the Rebellion. At a meeting of the S.C. Council in 1788, he said, "The Rebellion began in the North, and Northerners remain rebels at heart." When word of Bland's remarks reached Clinton, he protested to John Connolly, the Governor-General of the Southern Confederation, but Connolly did nothing. Clinton also noted Bland's participation in the Rebellion, and sneered that "our friend from Virginia is a man of great sensitivity. He left the rebel cause only a month after Saratoga. Had the victory not been won, today he would be toasting the health of General Gates and others of his stripe." Later, in 1790, Clinton remarked, "Here we are, situated between brothers in Quebec and the Southern Confederation, and both prepared to dismember us at the slightest provocation."

The clashes between North and South had deeper causes than the personalities of their leaders. There was little commerce between the two confederations; both sold most of their products to Europe, and the two confederations competed with each other for access to British investment capital. Sobel expresses surprise at the lack of cooperation between the various confederations of the C.N.A., but it could be argued that the Design was meant to isolate the confederations rather than unite them, the better to prevent the colonists from joining together in another Rebellion. The rivalry between the two confederations continued until the outbreak of the Trans-Oceanic War in 1795 brought them together to wage war on Spain's colonial dominions in North America.

Era of Harmonious Relations[]

Daniel Webster.

Initially the delegates to the N.C. Council represented the interests of merchants and large landowners, since these men tended to exercise the most influence over the confederation's restricted franchise. As wealthy factory owners appeared in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts in the early nineteenth century, however, they began to use their wealth to place their own men on the Council. These began to appear in 1814, and they pushed for legislation to raise tariffs, subsidize manufacturing, and encourage the formation of banks; By 1820 the Council's industrial cabal organized themselves into the Liberal Party, and went on to win control of the Council in the 1821 elections. The new Liberal majority selected Daniel Webster of Massachusetts as governor. Webster was a skillful politician, and under his leadership, the Council passed the Tariff of 1822, the Bank Bill of 1822, the Internal Improvements Bill of 1823, and the Harbors Act of 1823. Webster's crowning achievement during his first term was the creation of the Bank of the Northern Confederation, which was modeled on the Bank of England, with the power to manipulate the currency, usually to the advantage of the industrial class.

Passage of the Bank Bill encouraged the growth of a financial community based in Broad Street in New York City, including Ezra Hopkins' Manhattan Bank, Junius Morgan's Bank of New York, Henry Cowell's Fidelity Bank, and the financial businesses of Jacob Little, Samuel Slocomb and Homer Young. The most important result of the Liberals' legislative victories was the start of a railroad construction boom in the N.C. A major figure in the railroad boom of the 1820s was Cornelius Vanderbilt, the son of a ferryboat captain who created the Northern Confederation Central Railroad with financing from Cowell's bank. Vanderbilt and Cowell also created a major shipping line that dominated the trans-Atlantic shipping industry. Little focused his energies on the Southern Confederation, financing businesses throughout the S.C., to the point where he was regarded as the power behind the S.C.'s own Liberal Party, and Southern businessmen often complained of being under the control of "the New York interests."

Broad Street financing was also behind the creation of Malcolm McGregor's Society for Industry, a vertically integrated manufacturing center outside of Philadelphia that included mines, iron foundries, banks, and mercantile establishments. The workers in McGregor's Society for Industry not only worked for him, they also lived in his houses, and purchased goods and services from his shops with the company scrip they were paid. By the 1830s the term McGregorization was used to refer to the control of a whole region and all the people working there by a single company.

| RAILROAD | IRON | BANK | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEAR | MILEAGE | EXPORTS | IMPORTS | ORE | CAPITAL |

| 1810 | 0 | 15 | 60 | 60 | 10 |

| 1815 | 0 | 20 | 71 | 91 | 21 |

| 1820 | 0 | 40 | 103 | 187 | 36 |

| 1825 | 156 | 71 | 128 | 240 | 59 |

| 1830 | 967 | 85 | 137 | 258 | 88 |

| 1835 | 2,009 | 101 | 151 | 365 | 121 |

| 1840 | 4,448 | 115 | 179 | 457 | 130 |

(Source: C.N.A. Statistical Abstract, pp. 543, 687, 1179. Iron ore per 1,000 tons; exports, imports, and bank capital per million N.A. £.)

Martin van Buren.

The success of Webster and the Liberals led to the formation of a rival political party, the Conservative Party, representing the interests of farmers, urban workers, and small businessmen. Because they appealed to a larger electorate than the Liberals they were able to gain control of the Council in 1825, and Webster was replaced as governor by Conservative leader Martin van Buren. However, unlike the Liberals, the Conservatives had no coherent political philosophy, being committed to nothing more positive than the reversal of the Liberals' policies. The Conservatives had little legislative success, and van Buren's only accomplishment was to replace Webster's appointees to the B.N.C. with his own men. The Conservatives' own manipulation of the N.C.'s banking system was a major cause of the Depression of 1829, which brought the Liberals, and Webster, back to power in 1831.

After losing control of the Council, many Conservative groups abandoned politics. Urban workers formed a labor union called the Grand Consolidated Union which used strikes and other labor actions to agitate for better pay and working conditions. At the same time, the confederation's farmers formed the Freeholders' Alliance to seek currency inflation, anti-creditor laws, and the abolition of the Bank of the Northern Confederation.

Crisis Years[]

A financial crisis in London in late 1835 brought about the Panic of 1836, when a series of bank failures in New York brought an end to the prosperity of the N.C. Unemployment rose in Massachusetts textile factories, Pennsylvania foundries and mines, and the port cities of New York and Philadelphia. The growing hardship, combined with Webster's inability to maintain confidence in the N.C., led to rapid growth by the Grand Consolidated. Franz Freund, the founder of the Grand Consolidated, created a political party called the Laborers' Alliance which contested local and provincial elections in the N.C. Although the Liberals suffered several defeats, they were able to maintain their majority, and Webster was able to win a new vote of confidence and remained in office.

The political deadlock in the N.C. Council and continued high unemployment led the Grand Consolidated to launch a massive general strike in the summer of 1840. Several of the confederation's cities were dominated by mobs led by a radical underground group called the Sons of Liberty, as Webster lacked sufficient military strength to put them down. On 4 September 1840, Webster was stabbed by radical labor activist Matthew Hale as he walked home from the Hall of Justice. Webster died of his wounds three days later.

Henry Gilpin.

After Webster's death, the Council's Liberal majority chose Henry Gilpin of Pennsylvania to succeed him. Gilpin suspended the Britannic Design's civil liberties guarantees, and encouraged manufacturers to hire private armies to attack Consolidated headquarters' throughout the confederation. Gilpin excused the vigilante attacks by saying, "There is no room for violence in the N.C., but the situation is so critical that strong measures are needed." Gilpin also called up the confederation's provincial militias, who joined with the private armies to wipe out the Consolidated and the Laborers' Alliance. By March 1841, both organizations had been destroyed at the cost of over 40,000 killed and 78,000 seriously injured.

Gilpin continued to rule the N.C. by emergency decree until 1842, when the Liberals lost their majority on the Council, and John Dix of New York replaced Gilpin. Dix restored civil liberties and pledged an administration of "healing and humanitarianism, in which the rights of all will be protected."

Second Britannic Design[]

The disordered that struck the N.C. after the Panic of 1836 appeared in the C.N.A.'s other major confederations as well. John Calhoun of the S.C., who had long called for closer ties between the Liberal parties of the various confederations, arranged for a national convention of Liberals at Concordia, North Carolina in July 1841. Governor Gilpin led the N.C.'s delegation to the Concordia Convention, and in talks with Calhoun and General Winfield Scott of Indiana, he drafted a call for the Britannic Design to be revised to create a central government for the C.N.A.

The Conservatives of the four major confederations responded by holding their own convention in Brant, Indiana in August. Dix and Freund attended, and in the end the Conservatives echoed the Liberals' call for the creation of a central government. Viceroy Sir Alexander Haven forwarded the resolves of the two conventions to the government of Sir Duncan Amory in London. Amory and Queen Victoria both looked favorably on the proposals, and in January 1842 the House of Commons passed a bill authorizing a special meeting of the Grand Council to draft amendments to the Britannic Design.

At the Burgoyne Conference of July to September 1842, the delegates created what was essentially a new instrument of government for the C.N.A. The Grand Council itself would be remade into a directly elected body like the House of Commons, with 150 members being elected to five-year terms. A Confederation Senate would also be created to serve as an upper chamber, though with much more limited powers than the British House of Lords. The Grand Council would choose a Governor-General to serve as a national executive officer for the duration of its term, similar to the British Prime Minister. The Conference also adopted amendments affirming the C.N.A.'s membership in the British Empire, the British government's right to call upon the North American military, and the continued establishment of the Anglican Church in the C.N.A. The revised instrument of government, known as the Second Britannic Design, was confirmed by an Act of Parliament, and elections for the First Grand Council were scheduled for 14 February 1843.

Under the Second Design, the Northern Confederation elected 44 seats to the Grand Council, just under 30% of the total. On election day in 1843, the Unified Liberal Party won 31 seats and the National Conservative Party 13, which allowed the U.L.P. to win a 91 seat majority in the First Grand Council. The U.L.P. majority chose Scott as governor-general, and Scott appointed Gilpin as Minister of War.

Rocky Mountain War[]

Now that he had the resources of a strong central government to draw upon, Gilpin was determined to go to war with the U.S.M. Although Governor-General Scott opposed Gilpin's designs, he lacked both the resolution and the popular support among the Liberals to stop him. When copper and silver deposits were discovered in the poorly-defined border area between Vandalia and Mexico, Gilpin had his pretext for war. As the area filled with prospectors from both nations, disputes grew into conflicts, and both sides banded together into armed mobs. The settlements of Kinsey and Morelos were destroyed, and between February and June 1845 197 North Americans and 143 Mexicans were killed. Gilpin ordered North American troops into the border area, and on 4 September they clashed with Mexican troops. Scott had no choice but to authorize a general movement into the disputed area, and by the end of 1845 the Rocky Mountain War was in full force.

Bruce Harrison.

There were large sections of the population of the N.C. that opposed the war with Mexico, not least because it was Gilpin pursuing it. The early years of the war brought several sharp defeats for the C.N.A., and in 1848 the government in Burgoyne passed the C.N.A. first draft laws. The result was a series of anti-draft riots and strikes across the cities of the N.C., and Gilpin was forced to divert troops from the front to put down the uprisings. By 1849 there were more North American troops occupying the N.C. and Quebec than there were fighting the Mexicans.

Gilpin was dissatisfied with Scott's presecution of the war, and in April 1849 he resigned as Minister of War and called for a vote of no-confidence in Scott's leadership. Minority Leader Willie Lloyd of the S.C. joined Gilpin, and Scott lost the vote. However, instead of resigning, Scott spent three weeks trying to form a coalition government with a group of anti-war N.C.P. Councilmen. Not until the Unified Liberal caucus voted to expel him from the party did Scott resign. To Lloyd's disappointment, Gilpin was able to form his own coalition government with pro-War National Conservatives, averting national elections. As governor-general, Gilpin continued launching a series of attacks on the Mexicans, all of them unsuccessful.

By the end of the Second Grand Council in the winter of 1852-53, Gilpin had lost control of the Liberals, who chose his rival Bruce Harrison, Scott's former Minister of State, as their party leader. Harrison was unable to rally the Liberals, and on 15 February 1853 the Conservatives won 32 of the N.C.'s seats, giving them a 91-seat majority in the Grand Council. The new Conservative governor-general, William Johnson, agreed to an armistice with the Mexicans, and a peace treaty was eventually accepted by both countries in The Hague on 7 August 1855.

Urbanization and Reform[]

Kenneth Parkes.

In spite of the disruptions of the war, the industrial expansion of the N.C. continued. By 1880, over half of the confederation's population lived in urban centers of 50,000 or more. Immigrants from Great Britain, Ireland, and Europe continued to pour into the N.C., along with the children of Negro slaves from the S.C. freed in 1841, creating teaming slums that proved fertile ground for the appearance of street gangs, usually based on ethnic origin or race. In 1869, a predominantly Irish gang called the Merry Walkers led an uprising in New York, occupying City Hall for two weeks before the provincial militia was able to drive them out. Gangs in other N.C. cities copied the Merry Walkers, and during the 1870s life became hazardous in the cities.

As large businesses such as Thomas Scott's Grand National Railroad, Edwin Bromfield's North American Steel Corporation, and John Rockefeller's Consolidated Petroleum of North America appeared and grew, the industrial workers employed there formed labor unions such as Michael Harter's Mechanics National Union, William Richter's Consolidated Laborers Federation, and the New York-based United Workers of the World.

Politically, the N.C. became a bastion of the national Liberal Party. In the 1858 Grand Council elections the Liberals won 35 of the confiderations 44 seats, allowing party leader Kenneth Parkes of New York to win a 78-seat majority and the governor-generalship. However, winning 33 seats in the 1868 elections was not sufficient to allow Parkes' protégé, N.C. Governor Victor Astor, to maintain the Liberal majority. Electoral reforms enacted by Conservative Governor-General Herbert Clemens increased the N.C.'s delegation to the Grand Council to 45, but by enlarging the franchise in the Reform Bill of 1869, Clemens opened the door for a new party, the People's Coalition, to appear and grow by appealing to the newly-enfranchised voters. Richter founded a branch of the new party in the N.C., and in the 1873 elections the new party gained control of the legislature of New Hampshire province, as well as one of the N.C.'s Grand Council seats. Five years later, in spite of a surge of political violence directed against it by the older parties, the People's Coalition won ten of the N.C.'s Grand Council seats against the Liberals' 28, as well as 46 out of 131 seats in the Northern Confederation Council as against the Liberals' 59.

Scott Ruggles.

The coming of the Great Depression of the early 1880s brought renewed economic dislocations to the N.C., and gave the People's Coalition its second wind, allowing it to win eleven of the N.C.'s Grand Council seats, on its way to becoming the official Opposition, while the Liberals maintained their 28. P.C. party leader Scott Ruggles of the N.C. became Minority Leader, spending the next five years criticizing the policies of Liberal Governor-General John McDowell of Manitoba. By 1888, under Ruggles and Michigan City Mayor Ezra Gallivan, the P.C. had made itself the heart of the C.N.A.'s reform movement, and in that year's elections, won a 24-seat majority in the N.C. delegation, which lifted them past the Liberals to give them a 73-seat plurality in the Grand Council and putting Gallivan in office as governor-general.

Creative Nationalism and Starkism[]

The People's Coalition's constituency of urban industrial workers and small businessmen gave them a permanent majority in the Northern Confederation that endured until the waning years of the Diffusion Era in the 1930s. In that time, additional electoral reforms pursued by the P.C. under Gallivan and his successors extended the franchise further until the Reform Bill of 1898 brought the vote to all adult males, and the Reform Bill of 1908 extended the franchise to adult women. The P.C. also adopted a reform redrawing the Grand Council's electoral districts after every decennial census to reflect changes in the relative populations of the confederations. Under this reform the N.C.'s share of seats in the Grand Council fell steadily until reaching 32 seats in the 1930s and then rising to 35 in the 1940s.

A third reform of Gallivan's Creative Nationalism program that increased the P.C.'s constituency was the Fifth Point, which authorized the National Financial Administration to grant start-up loans to new businesses at interest rates below those offered by commercial banks. The Fifth Point created a new class of ambitious entrepreneurs; although most failed to obtain financing from the N.F.A., they were usually able to gain the funding they needed from commercial banks. Since the N.C. was the center of industrialization in the C.N.A., a majority of the new businesses financed by the Fifth Point were created there. As late as the 1920s, half of the start-up loans granted by the N.F.A. were in the Northern Confederation.

The least popular of Gallivan's policies was his isolationist foreign policy. In 1881 Mexico had come under the dictatorial rule of Chief of State Benito Hermión, and his imperialistic foreign policy, culminating in a successful war against the Russian Empire in the late 1890s, brought increasing anxiety to North Americans. In 1899 Councilman Fritz Stark accused Gallivan of accepting bribes from the Mexican corporation Kramer Associates to turn a blind eye to Hermión's aggression. Although Stark's charges were soon debunked, the result was a campaign of villification against Gallivan and violence directed at his allies, and against immigrants. Coalition headquarters in the cities of the N.C. and elsewhere were broken into, looted, and burned. In New York and Philadelphia mobs entered immigrant neighborhoods searching for "foreigners" who were sympathetic to "anti-North Americans." Across the C.N.A. 436 people were killed, thousands were seriously injured, and countless others were forced to flee their homes. A play opened in New York called "The Merry Life of Patrick Henry" that was a thinly-veiled attack on Gallivan, implying that he was guilty of terrible crimes. "The Merry Life" was an immediate hit and other productions opened elsewhere in the C.N.A.

The Starkist Terror continued until Gallivan resigned and Hermión was overthrown in 1901. A reaction quickly set in, and Gallivan's critics found themselves being fired from their positions in universities and newspapers, and ostracized by their former friends. The People's Coalition benefitted from the reaction, remaining in power until 1923.

Diffusion Era and After[]

The Coalitionist ascendancy was dealt what proved to be a fatal blow on 4 January 1916, when a mob of several thousand young people stormed the Federal Prison in Chapultepec, Mexico to free 8,000 Negro slaves who were being tried for treason during the Hundred Day War of 1914. Many turned out to be North American members of the abolitionist group Friends of Black Mexico.

The harsh retaliation against the F.B.M. members by the Confederation Bureau of Investigation sparked the New Radicalism, a growing dissident movement in the C.N.A. critical of the industrial civilization epitomized by the People's Coalition. After the abolition of slavery in Mexico, the F.B.M. was transformed into an anti-racism group called the League for Brotherhood that attracted various groups critical of industrialized society, including Ivan Falls' Agrarian Alliance and Arnold Gelb's Universities for Justice. The rise of the New Radicalism provoked a conservative reaction led by the Heirs of the Rebellion, and by the summer of 1922 the two sides were at each others' throats in a wave of political violence worse than the Starkist Terror.

A resolution to the social unrest was unexpectedly provided by the locomobile magnate Owen Galloway, who proposed a plan to end the turmoil by funding the emigration of the New Radicals within and from the C.N.A. Funding from the Galloway Trust allowed hundreds of thousands of people to flee the cities of the Northern Confederation for the endless empty prairies of Manitoba. From 1922 to 1925 the population of the N.C. fell from 35.5 million to 34.7 million, while Manitoba's rose from 21.0 million to 26.0 million. By 1930 the N.C.'s population had recovered to 35.6 million, while Manitoba's had risen to 31.5 million. After the 1930 census the N.C.'s share of seats in the Grand Council fell from 36 to 32, while Manitoba's rose from 23 to 27.

Elbert Childs.

Indiana Councilman Henderson Dewey of the Liberal Party was able to capitalize on the national mood of anti-urbanism to win a majority in the 1923 Grand Council elections. While maintaining the P.C.'s isolationist foreign policy, he reversed the centralization of power in the national government, transferring wealth and power to the individual confederations. The N.C. remained a Coalitionist stronghold for the time being, with Elbert Childs winning the governorship in 1923 while the P.C. held a narrow 19-17 majority in the Grand Council. However, such was Dewey's popularity that in 1928 Coalitionist party leader Frank Evans of the N.C. led the P.C. to their worst defeat since Gallivan's day, winning only 56 seats. After Dewey's death in 1929, his successor Douglas Watson reformed the N.F.A. to reapportion financings away from the industrialized confederations of the N.C. and Indiana to the rest of the nation, particularly Southern Vandalia and Manitoba. In the 1933 Grand Council elections, the Liberals were able to win a majority of the N.C.'s delegation for the first time in 50 years.

James Billington.

In his second term, Watson abandoned the C.N.A.'s traditional isolationism and openly supported closer ties with the United British Empire. This lost him much of his political support, particularly after Galloway came out against him. In the 1938 Grand Council elections, the People's Coalition again gained a majority of the N.C.'s delegation on the strength of Councilman Bruce Hogg's anti-military platform and his announcement that he intended to appoint N.C. Councilman James Billington, a prominent Negro, to the office of Council President. The P.C. maintained its majority in the N.C. for the next 20 years, until Liberal Governor-General Richard Mason won a narrow majority in 1958. By that time, regional differences in the C.N.A. had largely faded away, and partisan appeal had shifted to questions of social class and occupation, with the People's Coalition throughout the country appealing to businessmen, working-class voters, and science majors, while the Liberals appealed to professionals, the middle class, and humanities majors.

Notes[]

Sobel's sources for the history of the Northern Confederation are Daniel Webster's The Program for Progress (New York, 1838); Henry Gilpin's No Apologies Are In Order: My Term as Governor (New York, 1860); Joseph Clinton's The Life of George Clinton and the Clinton Family of the Northern Confederation (New York, 1882); Henry Gibbs' The Gilpin Legacy (New York, 1889); William Cocke's John Dix: The Great Healer (New York, 1905) and Caesar in Broadcloth (New York, 1910); Burgoyne Sloan's Origins of the Conservative Party in the Northern Confederation (New York, 1929); Albert Todd's Industry and Commerce in the Northern Confederation: 1810-1840 (New York, 1943); Andrew Shepard's The Northern Confederation in the Violent Years: 1835-1839 (New York, 1945); Milton O'Casey's I Never Told a Lie: The Political Career of Victor Astor (New York, 1950); William Reuss' The Origins of Unionism in the Northern Confederation (New York, 1950); Andrew Sloan's The Colossus of the East: The Rise of the Northern Confederation (New York, 1952); Edward Hetherington's Urban Riot: The Northern Confederation Cities in the 1870s, London, 1956); George Loring's The Right Man: Gilpin in Command (London, 1956); Esther Kronovet's New York in the Crisis Years: 1836-1837 (New York, 1960); Hugh Scott's Giant in Chains: Van Buren and the Conservatives (Mexico City, 1960); Robert Small's The Role of the Railroad in the History of the Northern Confederation (Mexico City, 1960); Chester Winslow's The Race Problem in the Northern Confederation (New York, 1965); Paul Brooks' Jacob Little and the Panic of 1836 (New York, 1967); Martin Denny's The Northern Confederation in the Era of Harmonious Relations (New York, 1967); James McCormick's The Anti-Liberals: Their Origins (New York, 1967); James Ripley's The Webster Legacy: The Creation of an Industrial Commonwealth (New York, 1967); Thomas Ripley's The Political Structure of the Northern Confederation in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (New York, 1967); Roberty Duffy's George Clinton: The New York Magician (New York, 1968); Max Finnigan's While the Iron is Hot: The Early Years of the U.W.W. (London, 1970); Henry Murray's edited Gilpin and the Historians (New York, 1970); and Thomas Rivers' Daniel Webster and His Confederation (New York, 1970).

This was the Featured Article for the month of January 2022.

| Confederations of the C.N.A. |

|---|

| Central Confederation • Indiana • Manitoba • Northern Confederation • Northern Vandalia • Quebec • Southern Confederation • Southern Vandalia • Vandalia |